A couple of years back, a good friend, or more precisely her publisher, suggested that she and I collaborate on a book about the cuisines of China’s Grand Canal.

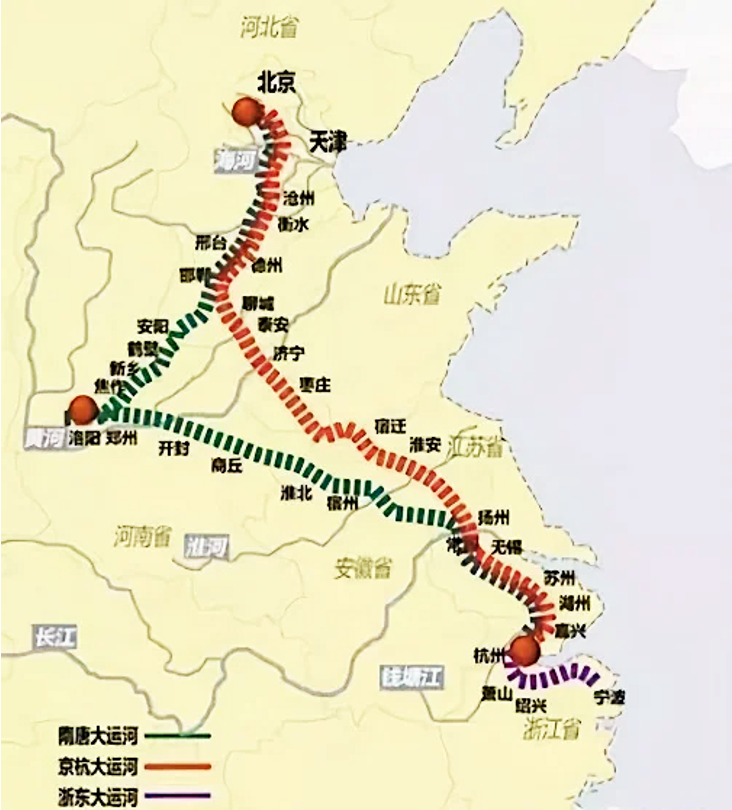

The Grand Canal is exactly what the name describes. It is indeed a canal and at just over 1800 kilometers long, makes a pretty solid case for being called “grand.” Using the conventions for naming railway lines, it is sometimes called the “Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal,” which is a mouthful, but gives you an idea of why this waterway was so consequential to China’s history.

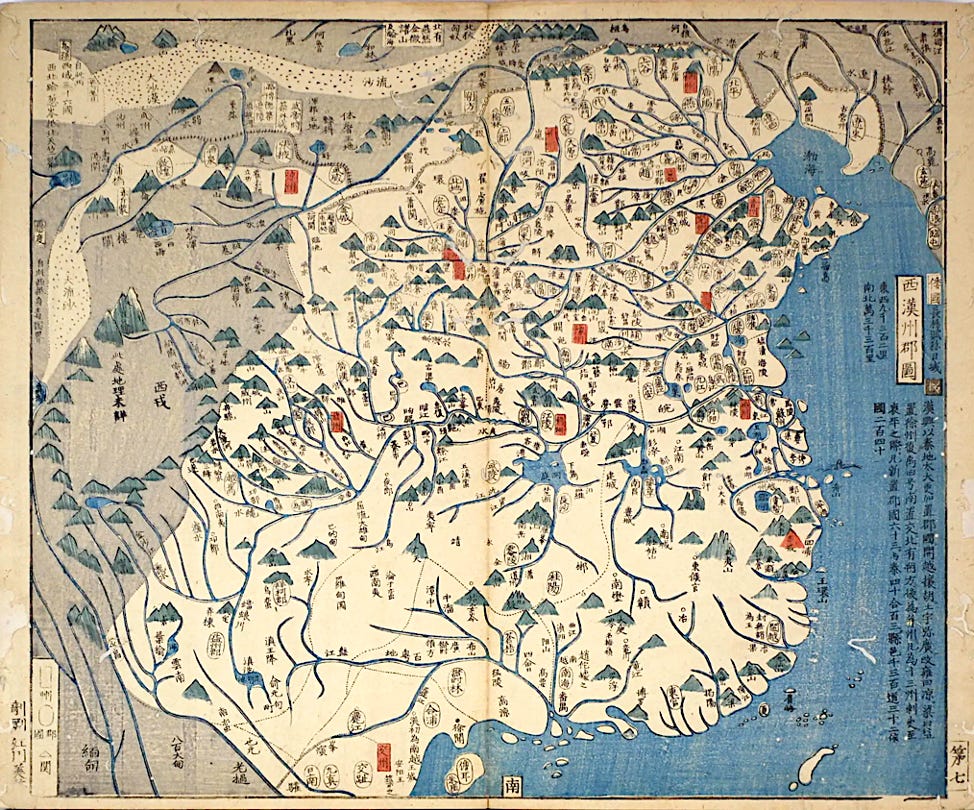

Most of China’s rivers flow from west to east. All of China’s large ancient cities were sited along these rivers. Commerce, culture, all that good stuff, historically flowed along with them as well.

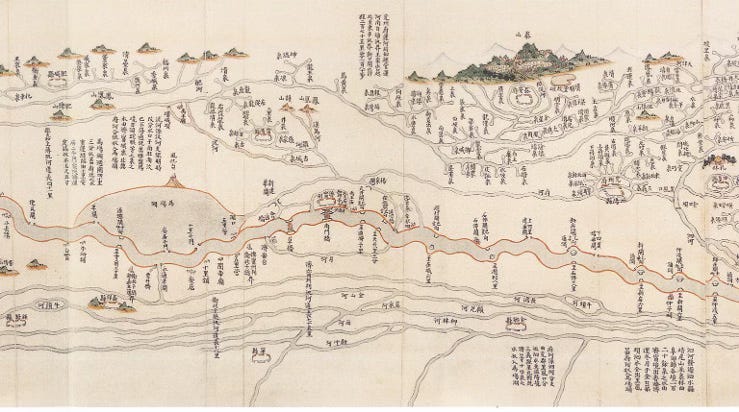

The Grand Canal, in contrast, runs north-south. The first iteration took it in a V shape, piggybacking onto natural waterways and cutting westward over to the Song capital at Bianliang. The course was later rerouted through Shandong to cut a much more direct path to the new capital at Beijing. Even after larger ships took to plying the open sea, the Canal remained a vital north-south highway for shorter trips and for shipping using traditional shallow-keeled barges.

Back in the late 1990s, I lived in a village that lay along the northern section of the Canal, which by that point was nothing more than a very long ditch that had been clogged up for as long as the oldest villagers could remember. Decades of intensive agriculture had drastically lowered the water table, and the famously soft Yellow River soil quickly flowed in to fill the gap. An elegant Ming-dynasty bridge spanning the muddy canal bed bore sole witness to what had once been a thriving commercial waterway.

Over recent years, China has devoted significant attention to getting the waterway back into operation, dredging the dried-up sections, and promoting the story of Grand Canal culture. My own university, along with pretty much every other research entity along the former path of the canal has been given resources to conduct research on the archeology and material life of the canal, and to collect cultural histories of people like the men who made their living pulling the boats from tracks along the shore. While the original boat pullers are mostly gone, their songs have been passed down to their descendants. These songs and stories find an enthusiastic market in books, films, and social media.

One problem with all this official support for cultural research is that it tends to produce a glorified narrative, less political in orientation than commercial. Local art forms and customs get transformed into salable products, stamped with the approving seal of “Intangible Cultural Heritage.”

Canal Cuisine

This is especially true for something like cuisine. Every place, down to the smallest village, will claim as its own some particular dish, often with some story about a famous person who passed through and praised their local wine, preserved vegetable, or way of cooking fish. Often that famous person is said to be the Qianlong emperor (1711-1799), who did indeed travel about the countryside in disguise, though the sheer number of legends about everything he supposedly ate would give the idea that he was primarily operating as an itinerant food critic.

So what did people along the Canal actually eat?

In some ways, the Grand Canal acted very much like historian Fernand Braudel’s image of the Mediterranean – a region surrounded and defined by water that effectively makes distance meaningless. The ancient megacity of Rome imported most of its grain from Egypt because it could—water made it possible to ship food cheaply and reliably. A landlocked city that had to grow its own food or cart tons of grain could never have grown to the size that Rome eventually would.

Officially speaking, China’s Grand Canal served a similar purpose. It was intended to serve the capital, wherever that capital happened to be, by acting as the conduit to ship plentiful southern rice up north, which is also where much of the military happened to be stationed. The Canal was also a route for bringing rare southern commodities up to the palace. Semi-tropical fruit like lychees could be packed into a saddle bag and just barely survive the 1800-kilometer journey, but more delicate products like fresh abalone had to be shipped on ice. That’s really only a job for ships.

But if official shipping, known as caoyun, pioneered the mechanisms for distance shipping, it was still only a matter of time before the general public got a taste. As is so often the case, the state was the prime mover for a technological change that would become more widespread. Using the same waterway that supplied the palace, merchants shipped tea, rice, sauces and spices to towns and villages all along the Canal.

Best known for its poetic sex scenes, the early 17th-century novel The Plum in the Golden Vase also contains a lot of eating. Tasty details like the bean and white rice porridge used as a hangover cure reveal how exotic Southern tastes had become completely commonplace in a very ordinary northern canal town. The novel’s main characters think nothing of their daily staples, produced thousands of kilometers away.

I’m most definitely still intrigued by the idea of writing a culinary history of this awesome waterway, but it won’t be based on the iconic dishes served in Beijing or Hangzhou, not all of it. The river of commerce and culture touched every little village that lay along its banks, making small changes to tastes and habits. Over hundreds of years, this snaking channel carried distinct customs, language, and cuisine to communities up and down its course, setting the waterfront communities apart from their inland neighbors. That’s the real story.