Structuralism and the successful dinner party

China is one of the world’s great and oldest literary civilizations. It is also one of the great culinary civilizations.

Put those together, and you get a truly vast body of Chinese food writing.

China’s earliest known food texts date back about 2500 years, and these draw on an oral tradition that is thousands of years older. This tradition would grow to include a wide variety of texts: agricultural, medical, and religious treatises, food-centered novels such as the Dream of the Red Chamber, and countless books and poems written in praise of the delicious.

Historians are quite adept at reading across genres. It’s no leap for us to juxtapose a 7th-century farming manual against a poem written five hundred years later. That sort of technique works best if what we are looking for is documentary proof of existence—evidence that something happened, that some invention had appeared, or that a particular crop was under cultivation.

China’s rich and diverse food writing offers something different. The sprawling body of texts not only crosses genres, it emerges as a genre in itself. Like any genre, China’s food writing is self-aware and self-referential. Writers would reach back to an ever-growing canon of classics, freely crossing lines between technical and artistic fields.

Which brings us to structuralism.

The term structuralism is used for a fairly broad array of ideas, but here I’m referring to the idea pioneered by people like sociologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, that humans create basic ideational structures to make sense of their world, for example breaking abstract phenomena into binary pairs (e.g., dark/light, wet/dry, raw/cooked). Some themes or structures are so fundamental that they go unnoticed, but they are vital for how we perceive the world. Explaining why we have so many metaphors about animals, Lévi-Strauss famously called them (animals) “good to think with.”

Folklorists have adapted these basic ideas to explain patterns like repeating motifs in folk art, why certain designs always appear in threes, for example. It doesn’t matter what you’re painting, there’s always going to be three of them. You can see certain basic patterns that cross architecture, drawing, storytelling and music—and in particular in the overlap between different modes of expression. The structure is deeper and more fundamental than the content.

Back to food writing, the question is how to see the big picture in a tradition that freely jumps genres. Looking back into China’s food history, we can deep dive into specific topics like flavors and techniques, medical theory, ritual practices, or what have you, but it’s important to remember that this sort of pareclized view is not how the writers themselves saw it.

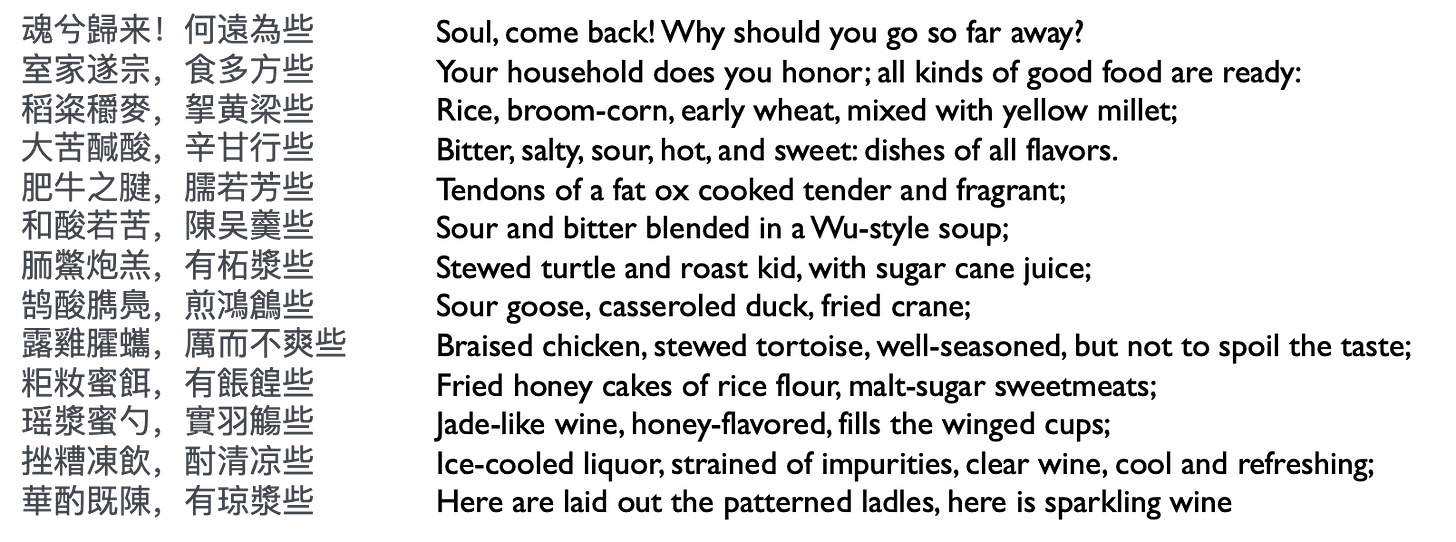

Have a gander at this imaginary feast:

This menu is extracted from “Calling the Soul” (招魂), a funerary poem indended to coax the soul of the deceased back to the world of the living. Recorded in a book called the Songs of Chu, this version was put to paper2 in the third or fourth century BC, but the oral (either spoken or sung) version is certainly much older.

On the surface, this is indeed a very fancy feast, just the sort that might make a soul think twice about moving on.

But it is so much more. The 2500-year-old menu distills elements of a medical and culinary theory that were already quite sophisticated.

It does so in a poem, using the conventions of poetry.

When Mark Twain (reputedly) said that “History never repeats itself, but it does often rhyme,” he was himself speaking poetically.

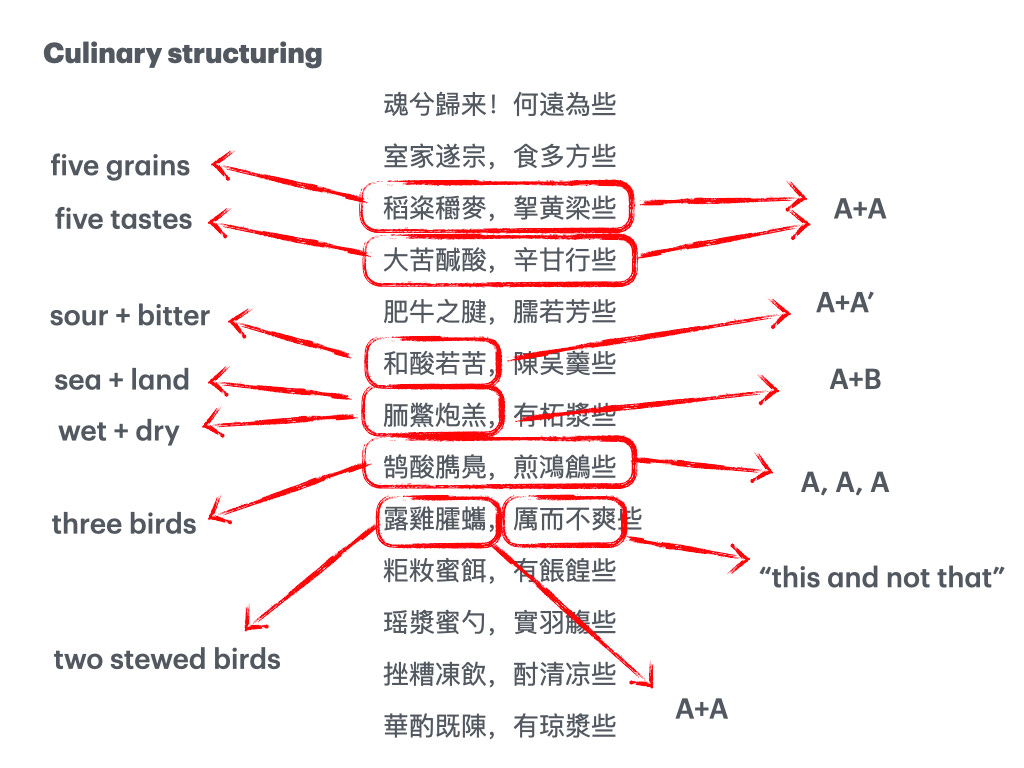

This menu does something more literal, using elements of poetic structure in its arrangement of foods. Five Grains 五谷 are matched against Five Tastes 五味. Flavors, ingredients, and techniques appear in opposing pairs, just like rhymes in a couplet. Other sections follow the similar patterns, writing the worldly pleasures of hunting or palace women into a structure that does with concepts what poetry does with sound.

A poem of ideas.