How to eat in China’s 13th season

Summer’s been brutal.

Crazy heat, lots of travel, plus of course all of the activity surrounding the publication of China in Seven Banquets: A Flavourful History.

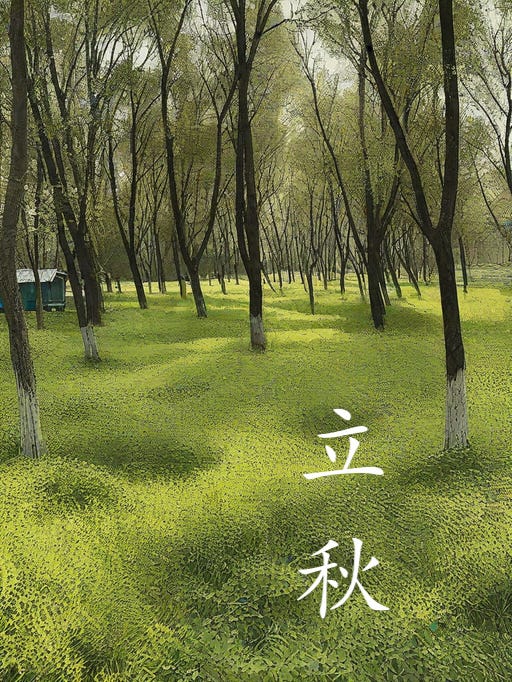

But summer’s now officially over. At least it is in Beijing, where we just marked the season of li qiu 立秋, the Beginning of Autumn.

Most of us think of only four seasons, but China gets six times as many. That’s twenty-four, for the less mathematically inclined, a new season roughly every two weeks. This calendar is sometimes called “solar terms,” which sounds like we should have a test at the end of each one. So “seasons” it is.

The Chinese calendar of seasons goes back millennia and has been used to measure everything from astronomy to the correct time to hold political ceremonies. But most people know it as an agricultural calendar, a Farmer’s Almanac, and an extremely precise one at that.

Subscribed

For weeks, Beijing was unbearable, alternating between blazing sunshine and torrential downpours that turned the whole city into a mosquito wonderland.

But the morning of li qiu, which this year was August 6, something had changed. The sky was a deeper blue, the leaves were a darker green, and the air was drier. The fever had broken.

A change of seasons means a change of diet. I’ll be adding more detail to this as time goes on, but in brief, people have to eat according to season. Not just because some foods are ready for harvest or because tradition demands it, but because the human body is part of nature and what it needs changes with the weather.

In summer, you eat “cooling” foods with a bitter taste. Bitter melon, also known as “cooling melon” is one of these—it draws out the body’s excess heat and moisture.

But you wouldn’t want bitter melon after li qiu because the world is slowly starting to dry out, and you don’t want to dry out with it.

So what should you eat in li qiu?

Some typical foods include:

- Moistening foods: sesame, honey, white fungus, dairy

- Strengthening foods: pumpkin, walnuts

- Foods to help the spleen and stomach: yam, chestnuts, dates, pears

After a fairly vegetarian summer, it’s now time to start going back to meat. Ask people here in Beijing what to eat on li qiu and they will tell you meat. One typical dish is steamed pig cheeks, which reaches your table as a fairly gelatinous looking piece of sliced meat. In market stalls it’s sold with the face displayed whole, more identifiably the part of the pig you might have once conversed with. Other seasonal dishes feature cuts of pork like trotters that have a lot of fat or cartilage

Another seasonal favorite is duck. Autumn duck are just starting to put on fat, which is just what we should be doing as well.

Here’s a very typical autumn dish

Autumn white fungus soup 银耳西米羹

- 100g white fungus, fresh or reconstituted, hand torn into large shreds

- 1/4 cup pearl sago, soaked overnight

- 6-8 dried red dates (halved if large)

- small handful goji berries

- rock sugar or honey to taste

Add all of the ingredients to a clay pot, add water to cover and cook at very low heat for about 30 minutes, stitrring occasionally and adding water as needed. Add the goji berries close to the end. The dish is done when the pearl sago is completely translucent and the soup has a thick, gelatinous texture. If do you wish to add a bit of sugar or honey, now’s the time to do it, but have a taste first, as you may find that additional sweetener is completely unnecessary. You can serve this warm or cold, either as the final dish of a meal or as a snack.

You can make a similar dish by swapping out the white fungus for Asian pears, peeled and cut into large chunks. Swap out the dates for a few very thin strips of dried tangerine peel. You could even make something similar using pears and nothing else. Slowly boiled pear concentrate makes another lovely, warming drink, enjoyed across northern China.

I’ll be adding new recipes for each season. Please share with your friends.